We’ve been watching 2016 television news coverage of violence at political rallies for presidential candidate Donald Trump and reading of how he pines for “the good old days” when aggression was met with aggression. It made me think of the Jaybird-Woodpecker War in which one of my cousins’ husbands was shot and killed by a political rival, the first of many deaths resulting from the quest for power in Reconstruction-era Texas.

After the Civil War, millions of slaves were suddenly freed persons. When the 15th Amendment gave black men the right to vote, the freedmen became a powerful Republican voting block. Fort Bend County, Texas, was one of the southern counties where freedmen outnumbered white men by as much as four to one, and their vote carried most elections, sustaining the political status quo. These administrations often included corruption and payoffs. On March 18, 1896, the Houston Post looked back on it this way:

Property owners and taxpayers were confronted with a condition similar to that which brought about the “Boston Tea Party,” and they were forced to bow to the will of the negro majority and pay exorbitant fees to officeholders whose maxim was “Public office is a private snap.” Taxation without representation was like the application of an acid to an unhealed wound, and in the summer of 1888 a movement was inaugurated for the purpose of bringing about a change in affairs for the betterment of the people.

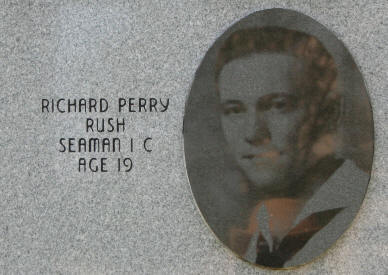

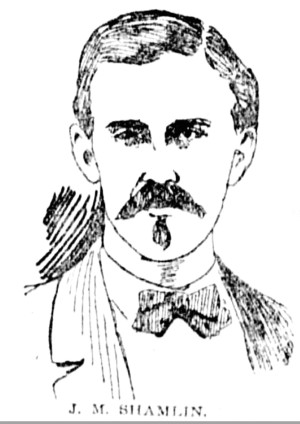

By the mid-1880s, many young men in Fort Bend County — including my cousin-in-law, J. M. Shamblin — were increasingly frustrated with politics-as-usual. James Madison Shamblin was born in Lumpkin, Georgia, in 1846, son of a farmer. By the early 1870s he had moved to Texas and in 1877 married Bettie Jane Fields, my third cousin three times removed. Her father was one of the largest cotton planters in the area southwest of Houston, and the Galveston Daily News referred to her husband as “one of Fort Bend’s best citizens and a prominent planter.”

The young men of Richmond, county seat of Fort Bend County, organized the Young Men’s Democratic association. Someone called them the Jaybirds, intending it as an insult, but the group proudly adopted the symbol and began calling themselves the Jaybirds. They called their Republican rivals the Woodpeckers. [I’m not gonna go there.]

].M. Shamblin was an active Jaybird who “went among the negroes attempting by reason and argument to convince them that the deplorable condition of affairs would result in no benefit to them or the others in the county” and that they should vote Democrat. These activities resulted in Shamblin’s murder with a double-barreled shotgun on the evening of August 2, 1888, as he sat at his Walnut Grove Plantation home with his wife and three children. A note was found on their gate which read, in part, “I am just from town and full of hell . . . I am a republican, and have no use for a damned democrat. This is a lesson to all damned cut-throat democrats to hold no more democratic meetings [with black people.]” The paper this note was written on was found to correspond to a leaf torn from a notebook belonging to Henry Caldwell, a freedman and Republican. Henry was arrested, tried in Houston, found guilty, and hung.

One month after Shamblin’s murder, another Jaybird, Henry Frost, was shot and wounded as he was returning home from closing his shop for the day. This fueled the antagonism, and the Jaybird-Woodpecker War was on.

Kyle Terry (Woodpecker) and Ned Gibson (Jaybird) were running against each other for the position of tax assessor in 1888. The two sides agreed to hold a series of political debates throughout Fort Bend County. Firearms were banned and the debates began peaceably. But on October 19, the gloves came off and Terry made a scathing personal attack on Gibson. [Is this starting to sound familiar now?] One of Gibson’s brothers pulled out a pistol; he was quickly disarmed, but emotions still ran high. As usual, the election was a victory for Terry and other Woodpecker candidates. The Woodpeckers were not gracious winners, and the Jaybirds were sore losers.

Not only did Terry beat Gibson at the polls, he beat Gibson up when he encountered him on the streets of Richmond after the election. The following spring, Gibson was scheduled to testify in a Wharton courthouse against a friend of Terry’s in a cattle-rustling case. But as Gibson left his hotel, Kyle Terry stepped out of a saloon, pointed his shotgun, and killed Gibson.

That did it! The Jaybirds were determined to get revenge for the shootings of Shamblin, Frost and Gibson . . . and they didn’t need much in the way of provocation. The Texas Rangers were sent to Richmond to keep the peace. On the afternoon of August 16, 1889, shots were exchanged between the Jaybirds and the Woodpeckers, who retreated to the county courthouse. The Jaybirds surrounded the courthouse and fired upon the Woodpeckers, who returned fire. Four Texas Rangers arrived but were outnumbered by the combatants on both sides. At the end of the 20-minute shoot-out, there were numerous dead and wounded. Someone recalled later that “enough shots had been fired to kill every man in town.”

The governor sent in the Houston Light Guard to control the situation and then came down himself to negotiate an end to the hostilities. It wasn’t long before most of the Woodpeckers left Fort Bend County. The Jaybirds were in power for the next 70 years.

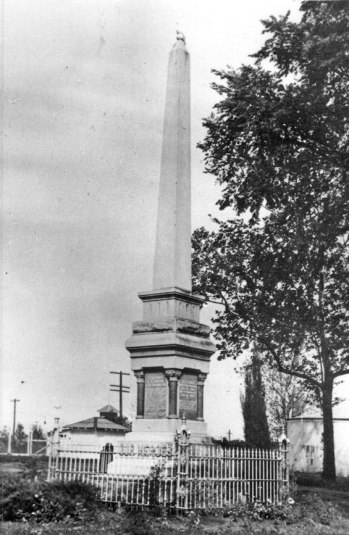

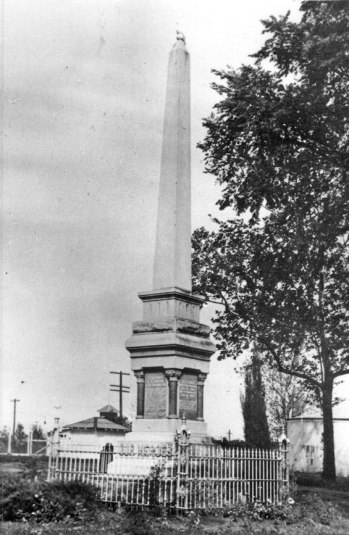

In 1896, plans were announced by the Jaybird Democratic Association that they would erect a monument to their heroes in the Jaybird-Woodpecker War. The monument would be of Texas gray granite and Italian Marble, approximately 35 feet high, on the southeast corner of the Richmond Courthouse property, with this inscription: “These brave and noble sons of Fort Bend county, whose names are here enshrined, gave their lives in order that the people of the county might have a just and capable county government, and their fellow citizens have reared this monument to their memory and as a promise to them that their principles shall be maintained for all time to come. Go, stranger, and to the Jaybirds tell that for their country’s freedom they fell. Our Heroes.” On the north side of the monument is this inscription:

“J. M. Shamblin

Born in Lamkin, Georgia,

December 18, 1846

Died in Fort Bend County, Texas

August 2, 1888

Oh, if there be on this earthly sphere

A boon, an offering, heaven holds dear,

‘Tis the last libation that Liberty draws

From the heart that bleeds and breaks in the cause.”

Well, I just hope and pray that America won’t see any monuments erected in the years following the 2016 election to Elephants or Donkeys, Woodpeckers or Jaybirds.