The Civil War was America’s bloodiest conflict. Roughly 2.5% of the country’s population at the time, an estimated 620,000 men, lost their lives in the line of duty. If you applied that percentage to today’s population, the toll would reach nearly 7 million. That’s staggering to contemplate!

Compare the number of Civil War casualties (620,000) to deaths in other American conflicts:

World War II – 405,399

WW I – 116,516

Vietnam – 58,209

Korea – 36,516

Revolutionary War – 25,000

Mexican War – 13, 283

Iraq-Afghanistan – 6,626

Spanish-American War – 2,446

Gulf War – 258

[Source: CivilWar.org ]

Approximately one in four Civil War soldiers never returned home. About 204,070 deaths occurred in or as a result of battles. For every three soldiers killed in battle, five more died of disease; but that is a topic for a future post.

In this blog I will tell the stories of some cousins who fought in the Civil War and perished as a result of action on the battlefield.

Roger Barton Jr. was born March 31, 1837, in Mississippi. He joined the 1st Mississippi Infantry, 4th Brigade, rising through the ranks to become adjutant of the 9th Regiment, Mississippi Infantry. Barton was wounded “near Cowan’s House” at the Battle of Stones River on December 31, 1862; he was taken prisoner and sent to Camp Chase in Ohio on March 25, 1863. On April 29 he was sent to City Point for a prisoner exchange. He then participated in the Battle of Jonesboro, Georgia, in which General William T. Sherman launched the attack that finally secured Atlanta, Georgia, for the Union. In late August of 1864, Sherman swung his army south of Atlanta to cut the main rail line supplying the Rebel army. Confederate General William Hardee’s corps moved to block Sherman at Jonesboro and attacked the Union troops on August 31, but the Rebels were thrown back with staggering losses, Lt. Barton among them. He was 27 years old. His name is inscribed on the tombstone of his parents in Holly Springs, Mississippi, in Hill Crest Cemetery. It reads:

To the kindred dust of Nature’s noble man,

we invoke the spirit of a valiant noble son.

Unarmed on Jonesboro’s desperate field he sleeps.

No monumental stone its faithful vigil keeps.

On those who fell on that blood dead Battlefield

a generous foe has set the everliving seal –

No prouder Epitaph can one engrave —

“Tread lightly, comrades. Here sleep the Brave.”

A truer Patriot, or a more patient Sage,

A stouter heart, of more mercurial gage –

Ne’er left his State for his Country’s good.

Or thence ascended to his Country’s God.

Barton grave

Benjamin “Berry” Broyles was born in Gallia Co., Ohio, in 1836. He joined Co. F of the 33rd Ohio Infantry and fought and died August 9, 1864, (age 28) in the Battlefield of “Utoy Creek,” west of Atlanta. Today, many earthworks and rifle pits still remain within the Cascade Springs Nature Preserve at 2800 Cascade Road in Atlanta. Broyles was buried in the Marietta National Cemetery.

The Marietta National Cemetery

Howard Kirtley Broyles was born in Madison Co., Virginia, in 1827. He enlisted in Fray’s Co. D, Virginia 34th Infantry. He was wounded in the neck on November 9, 1864, and died January 3, 1865, in Petersburg, Virginia, at the age of 38. He is buried at Blandford Cemetery in Petersburg, most likely on Memorial Hill in a mass grave consisting of 30,000 interments.

Memorial Hill Arch, inscribed “Awaiting the Reveille”

Marcellus Franklin Broyles was born in Greene Co., Tennessee, in 1837. He enlisted on March 4, 1862 and the next two years were filled with adventures and misadventures. He was captured at Fox’s Gap, Maryland, on September 14, 1862. Just a short time later, on October 2, 1862, he was released on a prisoner exchange. He fought at Gettysburg and was taken prisoner on July 2, 1863, and sent to Fort Delaware prison camp. On July 17 he was removed to a hospital in Chester, Pennsylvania; whether the transfer was due to a wound or to sickness is unknown. On October 4, 1863, he was sent to Point Lookout prison camp and was part of a prisoner exchange in early 1864. He went on to fight in the Battle of the Wilderness in northern Virginia, the first battle of the Civil War in which Grant and Lee fought each other. Broyles was killed in action on May 6, 1864, at age 26. There were 11,000 Confederate casualties in that action. His brother, William Lowndes Broyles, went to Virginia to claim the body and bring it home. It is said that when William returned with his brother’s body, he refused to come into the house because he was covered with lice; he took his clothes off in the yard and boiled them, and bathed outdoors before he would enter the house. The slain soldier was buried in the Sumach Cumberland Presbyterian Cemetery in Crandall, Georgia.

Maj. Gen. Wadsworth Fighting in the Wilderness (sketched by A. R. Waud)

Walker Broyles was born in 1832 in Virginia and fought in Co. A, 52nd Virginia Infantry. He died on June 27, 1862, fighting against federal troops at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill in Virginia; he was 30 years old. When you consider the numbers killed, wounded or missing in the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, it was the second bloodiest battle in American history. In an unexpected move, at 7:00 p.m., Lee unleashed upwards of 32,000 men – sixteen brigades – in a powerful assault against the Federal lines, likely the largest of the Civil War. Gen. George B. McClellan, commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, blamed his loss on lack of troops, writing to President Lincoln, “I feel too earnestly to-night, I have seen too many dead and wounded comrades, to feel otherwise than that the government has not sustained this army. If you do not do so now, the game is lost.. . If I save this army now, I tell you plainly that I owe no thanks to you, or to any other persons in Washington. You have done your best to sacrifice this army.” The Rebels had made their sacrifices, too, with 1,483 killed, 6,402 wounded, and 108 missing.

Union balloon Intrepid at the Gaines farm with gas generators at left. Captured by Confederates. (credit: Library of Congress)

Wilford Lee Harned was born in Kentucky on May 12, 1826. He served as a Kentucky state representative in 1857 and enlisted on October 1, 1861, in Bowling Green. He was commissioned an officer in Co. H, Kentucky 6th Mounted Infantry. Harned was mortally wounded in the Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee, in which there were 23,746 casualties. The book Tom Worthington’s Civil War: Shiloh, Sherman and the Search for Vindication describes the scene of April 6, 1862: “It seems that during the assault on the 46th Ohio, Capt. Harned kept sticking his head up from behind cover to monitor the enemy situation and keep an eye on his troops. One of his men had just urged him to keep his head down, but apparently Capt. Harned peeped once too often and took a round squarely through the forehead.” Harned died nine days later in Burnsville, Mississippi, at age 35.

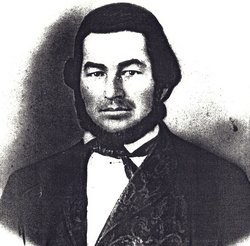

Capt. Wilford Lee Harned

Joseph Henry Yewell was born February 6 (my mother’s birthday) of 1837, in Nelson County, Kentucky. He enlisted in Co. A (Butler’s), 1st Regiment Kentucky Cavalry. As a 2nd Lieutenant, Yewell survived the Confederate loss at Missionary Ridge, Tennessee, in November 1863, and the troops retreated toward Dalton, Georgia. Brig. Gen. Patrick Cleburne was ordered to take a position in Ringgold Gap in north Georgia and delay Union forces on their way to Atlanta. Cleburne woke his troops, including Yewell’s 1st Kentucky Cavalry, at 3:00 in the morning on November 27, 1863, and marched to the head of Ringgold Gap, where with two cannon and 4,100 men he hoped to hold off three times as many Yankees. Cleburne watched the Union troops advance, instructing his men to hold artillery fire until the Federals reached the farm. According to one account, “Suddenly, Cleburne almost sprang into the air, clapped his knee and in his broad Irish brogue shouted ‘Now then boys, give it to ’em boys!’” From the way the Federal troops fell, with their hats, guns and equipment flying in the air, one of Cleburne’s men he said he had no doubt the whole line was annihilated, exclaiming, “By Jove, boys, it killed them all.” One observer said, “It was the dog-gondest fight of the war. The ground was piled with dead Yankees; they were piled in heaps . . . From the foot to the top of the hill was covered with the slain, all lying on their faces. It had the appearance of the roof of a house shingled with dead Yankees.” The battle earned Cleburne the nickname of “Stonewall of the West.”

But there were also 221 Confederate casualties. Lt. Yewell was wounded and hospitalized. Fannie A. Beers of Pensacola, Fla., was a Civil War nurse who served in Ringgold during part of the war. In her memoirs, published in 1889, she wrote: “The courthouse, one church, a warehouse and stores and hotels were converted into hospitals. Row after row of beds filled every ward. Upon them lay wrecks of humanity, pale as the dead, with sunken eyes, hollow cheeks and temples and long claw-like hands. Every train brought in squads of just such poor fellows…” The congregation of the last church not already used as a hospital refused to volunteer its use, so it was seized and straw put down for beds. Nurse Beers said that when an expected train arrived with 200 wounded, “there poured through the doors of that little church a train of human misery such as I never saw before or afterward during the war… They came, each revealing some form of acute disease, some tottering, but still on their feet, others borne on stretchers. Exhausted by forced marches over interminable miles of frozen ground or jagged rocks, destitute of rations, discouraged by failure, these poor fellows cast away one burden after another until they had not clothes sufficient to shield them from the chilling blasts of winter.”

This was the environment in which Lt. Yewell was treated; he died in Ringgold on January 26, 1864. The Anderson family cemetery was the resting place of many Civil War veterans, including 137 Confederate soldiers who died in Ringgold hospitals and were later moved to the Confederate Cemetery in Marietta, Georgia.

The online Museum of the Confederacy includes a photograph of a necklace belonging to Lucy Yewell, Joseph Yewell’s wife. The necklace is composed of beads made from human hair, with a locket. The locket has the engraved abbreviation: “K.S.H.T.W.S.S.T.” on one side (an indication that Joseph was a Freemason who had completed the degrees of the York Rite and was a “Royal Arch Mason”). On the other side is engraved “Sallie L. Yewell,” the name of their daughter. Inside the locket are two photographs (believed to be tintypes) of Lucy and Lt. Yewell.

Such bittersweet stories. I know my great-great-grandfather (my dad’s great-grandfather) enlisted in a South Georgia regiment and was captured at Gettysburg, then paroled in Maryland and surrendered at Appomattox, but I don’t know any of the details! However, I came across a recent posting by a third cousin on rootsweb.com that seems to hint he heard stories about the war from my great-aunt Lois, so maybe there’s hope I’ll learn more soon!

LikeLike

Let me know his name and I’ll look on my sources too.

LikeLiked by 1 person